Manuscript accepted on : September 16, 2008

Published online on: 14-03-2016

P. Praveen Kumar* and Y. Rajendra Prasad

*Hindu College of Pharmacy, Amaravathi Road, Guntur, University College of Pharmacy, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam India.

Corresponding Author E-mail: praveen_p26@yahoo.co.in

ABSTRACT: No other word endangers as much fear, revulsion, despair and utter helplessness as AIDS. AIDS is the collection of symptoms and infection resulting from specific damage to the immune system caused by HIV in humans. HIV is readily transmitted through blood apart from other body fluids and our profession involves abundant contact with the same. Many a time, HIV positive dental patient goes undetected not only due to “Window Period” of the infection, but also due to ignorance and negligence. Since the discovery of the virus, many new aspects about this virus has come into fore, which many of us need to be updated about. Oral lesions associated with HIV infection, as classified by the EC-Clearinghouse on Oral Problems related to HIV infection and the WHO Collaborating Centre on Oral manifestations of the immunodeficiency virus, were studied in 600 consecutive HIV-infected patients in Cape Town, South Africa.

KEYWORDS: AIDS; HIV; Oral manifestation and oral Diseases

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Kumar P. P, Prasad Y. R. Oral Manifestation of Aids. Biosci Biotechnol Res Asia 2008;5(2) |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Kumar P. P, Prasad Y. R. Oral Manifestation of Aids. Biosci Biotechnol Res Asia 2008;5(2). Biosci Biotechnol Res Asia 2008;5(2). Available from: https://www.biotech-asia.org/?p=7241 |

Introduction

AIDS

Most advanced stage of Human Immuno Deficiency Virus (HIV) infection.

Acquired not inherited

Immuno – attacks the immune system

Deficiency by destroying certain WBC’s

Syndrome – Group of symptoms that occur as a result of HIV infection

Epidemiology

1st case detected in Brazil in 1982

1st case in India in 1986 (Chennai)

5.2 million infections estimated (end 2005)

Max : Transmission – Heterosexual contact

Male : Female= 3:1

HIV 1 subtype C most prevalent

14,000 new infections per day

3.6 million deaths in 2005

Sources of Infection

Infected Blood, Semen, Vaginal fluids

Infected Breast Milk …..?????

Saliva and tears – epidemiologically insignificant

Exposure to tears, sweat, urine, feaces and saliva of an infected person is normally NOT considered as an “EXPOSURE” unless these secretions contain visible blood. HIV enters the host cell and uses parts of the CD4 cells to make more viruses (Replication) thereby killing the CD4 cells in process.

Oral Disease

It is frequently associated with HIV. While nearly all oral disorders associated with HIV infection also occur in other conditions characterized by immunosuppression, no other condition is associated with as wide and significant a spectrum of oral disease as HIV infection. Many HIV associated oral disorders occur early in HIV infection, not frequently as presenting sign or symptom. Thus early detection of associated oral disease should, in many cases, result in earlier diagnosis of HIV infection. Likewise, awareness of variety of oral disorders which can develop throughout the course of HIV infection, and coordination of health care services between physician and dentist, should improve overall health and comfort of patient.

No particular oral lesion is uniquely associated with HIV infection. However, the presence of one or more lesions requires that HIV infection be considered as a possible underlying cause. Some oral lesions, such as oral Candidiasis and oral hairy lukoplakia are strongly associated with HIV infection. Indeed, the emergence of one or more oral lesions correlates highly with HIV progression. A CD4 lymphocyte count of less than 200/mm3 is a reliable prognosticator of active disease and probability of shortened lifespan.

Classification of the Most Common Oral Manifestations of Aids

Bacterial Infections

Linear erythematous gingivitis (LEG)

Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (NUP)

Bacillary Epithelioid Angiomatosis (BEA)

Fungal Infections

Candidiasis

Pseudomembranous

Hyperplastic

Erythematous

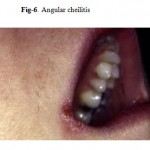

Angular cheilitis

Viral Infections

Epstein – Barr Virus (Oral Hairy lukoplakia)

Herpes Simplex Virus

Cytomegalovirus

Human Pailloma Virus

Neoplasms

Kaposi’s sarcoma

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL)

Other Oral Lesions

Major aphthous ulceration

Necrotizing stomatitis

Bacterial Infections

Linear Erythematous Gingivitis (Leg)

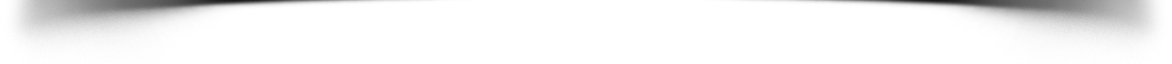

This entity, previously known as HIV associated gingivitis, is characterized by an erythematous band that follows that counter of the free gingival with a typical chevron appearance. The attached gingival is the site of an inflammatory reaction composed of petechia-like macules also having a reddish cue. Spontaneous bleeding is a frequent finding. The erythematous inflammatory band is a result of bacterial proliferation in the gingival sulcus.the most frequently found microorganisms in this lesion are: Bacteroides gingivalis, Bacteroides intermedius, Actinomyces viscous, Fusobacterium nucleatum and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitants, among others. LEG is seen in patients with increased immunosuppression and as a rule is not associated with pain but is considered a potential precursor of necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis. .LEG does not respond to the usual therapeutic methods utilized to treat other types of gingivitis not associated to HIV infection.This entity appears as a 1–3 mm band of marginal gingival erythema, often with petechiae (Fig. 1). It is typically associated with no symptoms or only mild gingival bleeding and mild pain. Histological examination fails to reveal any significant inflammatory response, suggesting that the lesions represent an incomplete (aborted) inflammatory response, principally with only hyperemia present. There is no evidence to suggest that this entity will proceed to the far more destructive necrotizing periodontitis. Unlike conventional gingivitis, the erythema often persists following simple dental prophylaxis.

|

Figure 1: Linear erythematous gingivitis.

|

Necrotizing Ulcerative Periodontitis (Nup)

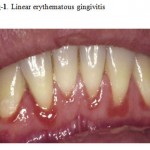

This unique periodontal lesion is characterized by generalized deep osseous pain, significant erythema that is often associated with spontaneous bleeding, and rapidly progressive destruction of the periodontal attachment and bone (Fig. 2). The destruction is not self-limiting and can result in loss of the entire alveolar process in the involved area. This very painful associated lesion adversely affects oral intake of food, resulting in significant and rapid weight loss. Because the periodontal microflora is no different from that seen in healthy patients, the lesion probably results from the altered immune response in HIV infection. More than 95% of patients with NUP have a CD4 lymphocyte count of less than 200/mm3 .

|

Figure 2: Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis.

|

Bacillary Epithelioid Angiomatosis (Bea)

This recently described lesion appears to be unique to HIV infection and is often clinically indistinguishable from oral Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS). Since both may present as an erythematous, soft mass which may bleed upon gentle manipulation, biopsy and histological examination are required to distinguish BEA from KS. The presumed etiological pathogen, Rochalimaea henselae, can be identified using Warthin-Starry staining. Both KS and BEA are histologically characterized by atypical vascular channels, extravasated red blood cells, and inflammatory cells. However, prominent spindle cells and mitotic figures occur only in KS.

Viral Infections

Herpes virus accounts for the majority of HIV-related oral viral infections, most frequently as recurrent oral herpes due to herpes simplex virus (HSV) or Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-induced oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL). Less commonly occurring viral infections involving the oral cavity include cytomegalovirus and human papilloma virus.

Oral Hairy Leukoplakia (Ohl)

Although originally postulated to be pathognomonic for HIV infection, this lesion has subsequently been reported in other immune deficiency states as well as in immunocompetent individuals. It appears as an asymptomatic adherent white patch with vertical corrugations, most commonly on the lateral borders of the tongue (Fig. 3). It may infrequently be confused with hypertrophic candidiasis and is predominantly found in homosexual males. Oral hairy leukoplakia has since been shown to be associated with a localized Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection and occurs most commonly in individuals whose CD4 lymphocyte count is less than 200/mm3 . While the diagnosis is most often clinical, histological inspection will reveal typical epithelial hyperplasia suggestive of EBV infection. This asymptomatic lesion does not require treatment. However, for cosmetic purposes, some patients may request treatment.

|

Figure 3: Oral hairy leukoplakia.

|

Herpes Simplex Virus

Intraoral herpes in healthy individuals results in multiple, small, shallow ulcerations with irregular raised white borders. Small clusters of lesions usually coalesce to form a larger ulcer, which heals uneventfully in 7–10 days. While the prevalence of seropositive HSV and the rate of reactivation is similar among both HIV-infected and non-infected populations, estimated to be 60% for those older than 30 years of age, recurrent intraoral HSV in patients with HIV infection often results in ulceration and pain of longer duration . Recurrent intraoral HSV lesions occur more commonly on poorly keratinized tissue like the buccal and labial mucosa, an uncommon site in healthy individuals. The pain associated with persistent herpetic ulceration can result in reduced oral intake of food and significant weight loss. Clinical diagnosis can be assisted by culture and examination of a cytologic smear for the virus. Culture results should be interpreted with caution due to the high HSV seropositivity and the potential for false negative results due to silent shedding of HSV.

Cytomegalovirus (Cmv)

It is necessary to recognize oral CMV, which is an uncommon cause of intraoral ulceration in patients with HIV disease. Such a lesion may represent an early sign of disseminated CMV infection. Disseminated CMV infection must be diagnosed as early as possible because of the serious nature of its sequelae, including retinitis and meningitis. CMV has been detected postmortem in one or more organ systems in as many as 90% of patients with AIDS. Oral CMV infection typically appears as a solitary, chronic deep ulceration most often involving the buccal and labial mucosa. Clinically, it is indistinguishable from other nonspecific ulcerations such as chronic HSV and major aphthous ulceration.

Human Papilloma Virus (Hpv)

In some patients with HIV infection, HPV causes a focal epithelial and connective tissue hyperplasia, forming an oral wart. More than 50 strains of HPV exist. The most common genotypes found in the mouth of patients with HIV infection are 2, 6, 11, 13, 16 and 32.

Neoplasms

Kaposi’s Sarcoma (Ks)

Kaposi’s sarcoma is the most common intraoral malignancy associated with HIV infection Recognition of the lesion is essential, since oral KS is often the first manifestation of the disease and is a diagnostic criterion for AIDS. The lesion may appear as a red-purple macule, an ulcer, or as a nodule or mass. Intraoral KS occurs on the heavily keratinized mucosa, the palate being the site in more than 90% of reported cases (Fig. 4). How ever, lesions have also been reported on the gingivene, tongue and buccal mucosa. The skin should also be examined for lesions whenever oral lesions are discovered. KS is especially common among homosexual and bisexual males and is rarely found in HIV-infected women.

|

Figure 4: Kaposi’s sarcoma.

|

Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (Nhl)

NHL is the most common lymphoma associated with HIV infection and is usually seen in late stages with CD4 lymphocyte counts of less than 100/mm3. It appears as a rapidly enlarging mass, less commonly as an ulcer or plaque, and most commonly on the palate or gingivae. NHL may be indistinguishable from masses caused by KS or other diseases in HIV-infected patients. Histological examination is essential for diagnosis and staging. Prognosis is poor, with mean survival time of less than one year, despite treatment with multi-drug chemotherapy.

Fungal Infections

Candidiasis

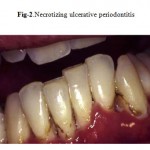

The most common HIV-related oral lesion is candidiasis, predominantly due to Candida albicans. While Candida can be isolated from 30–50% of the oral cavities of healthy adults, making it a constituent of the normal oral flora, clinical oral candidiasis rarely occurs in healthy patients. In stark contrast, clinical oral candidiasis has been reported to occur in 17–43% of patients with HIV infection and in more than 90% of patients with AIDS. One report found that unexplained oral candidiasis in healthy adults with risk factors for HIV infection predicted the development of clinical signs of AIDS within 3 months. Based on clinical appearance, oral candidiasis can appear as one of four distinct clinical entities: erythematous or atrophic candidiasis, pseudomembranous candidiasis (Fig-5,5a), hyperplastic or chronic candidiasis, and angular cheilitis. (Fig. 6).

|

Figure 5: Pseudomembranous candidiasis.

|

|

Figure 5a: Pseudomembranous candidiasis.

|

|

Figure 6: Angular cheilitis.

|

Other Oral Lesions

Major Aphthous Ulceration

Major aphthous ulceration is the most common immune-mediated HIV-related oral disorder, with a prevalence of approximately 2–3% The large solitary or multiple, chronic, deep, painful ulcerations of major aphthae appear identical to those in non-infected patients, but they often last much longer and are less responsive to therapy

(Fig. 7, 8).

|

Figure 7: Aphthous ulceration.

|

|

Figure 8: Aphthous ulceration.

Click here to View figure |

Necrotizing Stomatitis

Necrotizing stomatitis is an uncommon acute, painful ulceration which often exposes underlying bone and leads to considerable tissue destruction. This lesion may be a variant of major aphthous ulceration, but occurs in areas overlying bone and is associated with severe immune deterioration. Unlike necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis, the lesion may occur in edentulous areas.

Conclusion

Oral conditions seen in association with HIV disease are still quite prevalent and clinically significant. A thorough examination of the oral cavity can easily detect most of the common lesions. An understanding of the recognition, significance, and treatment of said lesions by primary health care providers is essential for the health and well-being of people living with HIV disease

References

- EC-Clearinghouse on Oral Problems Related to HIV Infection and WHO Collaborating Centre on Oral Manifestations of the Immunodeficiency Virus. Classification and diagnostic criteria for oral lesions in HIV infection. J Oral Pathol Med 1993; 22:289-291.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1992 Dec 18; 41(RR-17):1-19.

- Begg MD, Lamster IB, Panageas KS, et al. A prospective study of oral lesions and their predictive value for progression of HIV disease. Oral Dis 1997; 3:176-183.

- Glick M. Evaluation of prognosis and survival of HIV infected patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1992; 74:386-392.

- Glick M, Muzyka BC, Lurie D, Salkin LM. Oral manifestations associated with HIV disease as markers for immune suppression and AIDS. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1994; 77:344-349.Oral Manifestations of HIV Disease— Sirois

- Glick M, Lurie D, Salkin LM, Muzyka B. Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis: A marker for immune deterioration and a predictor for the diagnosis of AIDS. J Periodontol 1994; 65(5):393-397.

- Begg MD, Panageas KS, Lamster IB. Oral lesions as markers of severe immunosuppression in HIV-infected homosexual men and injection drug users. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1996; 82:276-283.

- Ramos-Gomez FJ, Maldonado YA, Greenspan JS, et al. Risk factors for HIV-related orofacial soft-tissue manifestations in children. Pediatr Dent 1996; 18(2):121-126.

- Lamster IB, Phelan JA, Zambon JJ, et al. Oral manifestations of HIV infection in homosexual men and intravenous drug users. Study design and relationship of epidemiologic, clinical, and immunological parameters to oral lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1994; 78(2):163-174.

- Shiboski CH, Cohen JB, Katz MH, et al. HIV-related oral manifestations in two cohorts of women in San Francisco. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1994; 7(9):964-971.

- Ficarra G, Rafanelli D, Piluso S, et al. Oral Lesions among HIV-infected hemophiliacs. A study of 54 patients. Haematologica 1994; 79(2):148-153.

- Hilton JF, Greenspan JS, Greenspan D, et al. Development of oral lesions in human. Immunodeficiency virus-infected transfusion recipients and hemophiliacs. Am J Epidemiol 1997; 145(2):164-174.

- Brawner DL, Cutler JE. Oral Candida albicans isolates from nonhospitalized normal carriers, immunocompetent hospitalized patients, and immunocompromised patients with or without acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Clin Microbiol 1989; 27:1335-1341.

- Thomas I. Superficial and deep candidosis. Int J Dermatol 1993; 32:778-783.

- Brawner DL Hovan AJ. Oral candidiasis in HIV-infected patients. Curr Top Med Mycol 1995; 6:113-125.

- Korting HC, Ollert M, Georgii A, Froschl M. In vitro susceptibilities and biotypes of Candidaalbicans isolates from the oral cavity of patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus.J Clin Microbiol 1989; 26:2626-2631.

- Tsang PC, Porter SR, Scully C, et al. Biotypes of oral Candida albicans isolates in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients from diverse geographic locations. J Oral Pathol Med 1995; 24(1):32-36.Oral Manifestations of HIV Disease— Sirois Samaranayake LP. Oral mycoses in HIV infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1992; 73:171-180.

- Klein RS, Harris CA, Butkus Small C, et al. Oral candidiasis in high-risk patients as the initial manifestation of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Eng J Med 1984; 311:354-358.

- Mooney M, Thomas I, Sirois DA. Oral candidiasis. Int J Dermatol 1995; 34:759-765.

- Giuliana G, Pizzo G, Milici ME, et al. In vitro antifungal properties of mouthrinses containing antimicrobial agents. J Periodontol 1997; 68:729-733.

- Epstein JB, Vickars L, Spinelli J, Reece D. Efficacy of chlorhexidine and nystatin rinses in the prevention of oral complications in leukemia and bone marrow transplantation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1992; 73:682-689.

- Eversole LR. Viral infections of the head and neck among HIV sero-positive patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1992; 73:155-163.

- Cowan FM, Johnson AM, Ashley R, et al. Relationship between antibodies to herpes simplex virus and symptoms of HSV infection. J Infect Dis 1996; 174:470-475.

- Oliver L, Wald A, Kim M, et al. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus infections in a family medicine clinic. Arch Fam Med 1995; 4:228-232.

- Fleming DT, McQuillan GM, Johnson RE, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 2 in the United States, 1976 to 1994. N Engl J Med 1997 Oct 16; 337(16):1105-1111.

- Annunziato PW, Gershon A. Herpes simplex virus infections. Pediatr Rev 1996 Dec; 17(12):415-423.

- Spruance SL, Crumpacker CS, Overall JC. Treatment of herpes simplex labialis with topical acyclovir in polyethylene glycol. J Infect Dis 1982; 146:85-90.

- Spruance SL, Crumpacker CS, Schnipper LE. Early, patient-initiated treatment of herpes simplex labialis with topical 10% acyclovir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1984; 25:553-555.

- Raborn GW, McGaw WT, Grace M, Houle L. Herpes labialis treatment with acyclovir 5% ointment. J Can Dent Assoc 1989; 55:135-137.

- Fiddian AP, Ivanyi L. Topical acyclovir in the management of recurrent herpes labialis. Br JDermatol 1983; 109:321-326.

- Cartledge JD, Midgley J, Gazzard BG. Non-albicans oral candidosis in HIV-positive patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 999; 43:419-422.

- Maenza JR, Keruly JC, Moore RD. Risk factors for fluconazole-resistant candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J Infect Dis. 1996; 173:219-225.

- Spruance SL, Rea TL, Thoming C, et al. Penciclovir cream for the treatment of herpes simplex labialis. JAMA 1997; 277:1374-1379.

- Greenspan D, Greenspan JS, Conant M, et al. Oral “hairy” leukoplakia in male homosexuals: Evidence of association with pappilomavirus and a herpes-group virus. Lancet 1984; 2:831-834.

- Syrjanen S, Laine P, Happonen RP, Niemela M. Oral hairy leukoplakia is not a specific sign of HIV infection but related to immunosuppression in general. J Oral Pathol Med 1989; 18:28-31.

- Felix DH, Watret K, Wray D, Southam JC. Hairy leukoplakia in an HIV-negative,nonimmunosuppressed patient. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1992; 74:563-566.

- Glick M, Pliskin ME. Regression of oral hairy leukoplakia after oral administration of acyclovir. Gen Dent 1990; 38:374-375.

- Greenspan JS, Greenspan D. Oral hairy leukoplakia: Diagnosis and management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1989; 67:396-403.

- Lozada-Nur F. Podophyllum resin 25% for treatment of oral hairy leukoplakia: An old treatment for a new lesion. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1991; 4:543-546.

- Jones AC, Freedman PD, Phelan JA, et al. Cytomegalovirus infections of the oral cavity. A report of six cases and a review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1993; 75:76-85.

- Drew WL, Sweet ES, Miner RC, Mocarski ES. Multiple infections by cytomegalovirus in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: Documentation with Southern blot hybridization. J Infect Dis 1984; 150:952-953.

- Moore LVH, Moore WEC, Riley C, et al. Periodontal microflora of HIV positive subjects with gingivitis or adult periodontitis. J Periodontol 1993; 64:48-56.

- Zambon JJ, Reynolds HS, Genco RJ. Studies of the subgingival microflora in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Periodontol 1990; 61:699-704.

- Cockerell CJ, Whitlow MA, Webster GF, Friedman-Klien AE. Epithelioid angiomatosis: A distinct vascular disorder in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or AIDSrelated complex. Lancet 1987; 2:654-656.

- Oral Manifestations of HIV Disease— Sirois Glick M, Cleveland D. Oral mucosal bacillary (epithelioid) angiomatosis in a patient with AIDS associated with rapid alveolar bone loss — Report of a case. J Oral Pathol Med 1993; 22:235-239.

- Feigal DW, Katz MH, Greenspan D. The prevalence of oral lesions in HIV-infected homosexual and bisexual men: Three San Francisco cohorts. AIDS 1991; 5:519-525.

- Flaitz CM, Su IJ, Wang YW, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpes virus-like DNA sequences (KSHV/HHV-8) in oral AIDS-Kaposi’s sarcoma: A PCR and clinicopathologic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1997 Feb; 83(2):259-264.

- Mocroft A, Phillips AN, Halai R, et al. Anti-herpes virus treatment and risk of Kaposi’s sarcoma in HIV infection. Royal Free/Chelsea and Westminster Hospitals Collaborative Group. AIDS 1996 Sep; 10(10):1101-1105.

- Phelan JA, Eisig S, Freedman PD, et al. Major aphthous-like ulcers in patients with AIDS. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1991; 71:68-72.

- Muzyka BC, Glick M. Major oral ulcerations in HIV disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1994; 77:116-120.

- Schrot RJ, Adelman HM, Linden CN, Wallach PM. Cystic parotid gland enlargement in HIV disease. The diffuse infiltrative lymphocytosis syndrome. JAMA 1997 Jul 9; 278(2):166-167.

- Seddon BM, Padley SP, Gazzard BG. Differential diagnosis of parotid masses in HIV positive men: Report of five cases and review. Int J STD AIDS 1996 May-Jun; 7(3):224-227.

- Greenberg MS, Glick M, Nghiem L, et al. Relationship of cytomegalovirus to salivary gland dysfunction in HIV-infected patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1997 Mar; 83(3):334-339.

- Hewitt DJ, McDougald M, Portenoy RK, et al. Pain syndromes and etiologies in ambulatory AIDS patients. Pain 1997; 70:117-123.

- Breitbart W, McDougald M, Rosenfeld B, et al. Pain in ambulatory AIDS patients. I: Pain characteristics and medical correlates. Pain 1996; 68:315-321.

- Breitbart W. Pain in AIDS. In: Jensen TS, Turner JA, Weisenfeld-Hallin Z, editors.Proceedings of the 8th World Congress on Pain. Progress in pain research and management,Vol. 8. Seattle (WA): IASP Press; 1997. pp. 63-100.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1993 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1993 Sep 24; 42(RR-14):1-102.

- Oral Manifestations of HIV Disease— Sirois Serrano M, Bellas C, Campo E, et al. Hodgkin’s disease in patients with antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus. Cancer 1990; 65:2248-2254.

- Glick M, Muzyka BC. Alternative therapies for major aphthous ulcers. J Am Dent Assoc 1992; 123(7):61-65.

- Jacobson JM, Greenspan JS, Spritzler J, et al. Thalidomide for the treatment of oral aphthous ulcers in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases AIDS Clinical Trials Group. N Engl J Med 1997; 336(21):1487-1493.

- Yeung SC. HIV infection and periodontal disease. Ann R Australas Coll Dent Surg. 2000; 15:331-334.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.